“Craftivism”: The Art of Craft and Activism

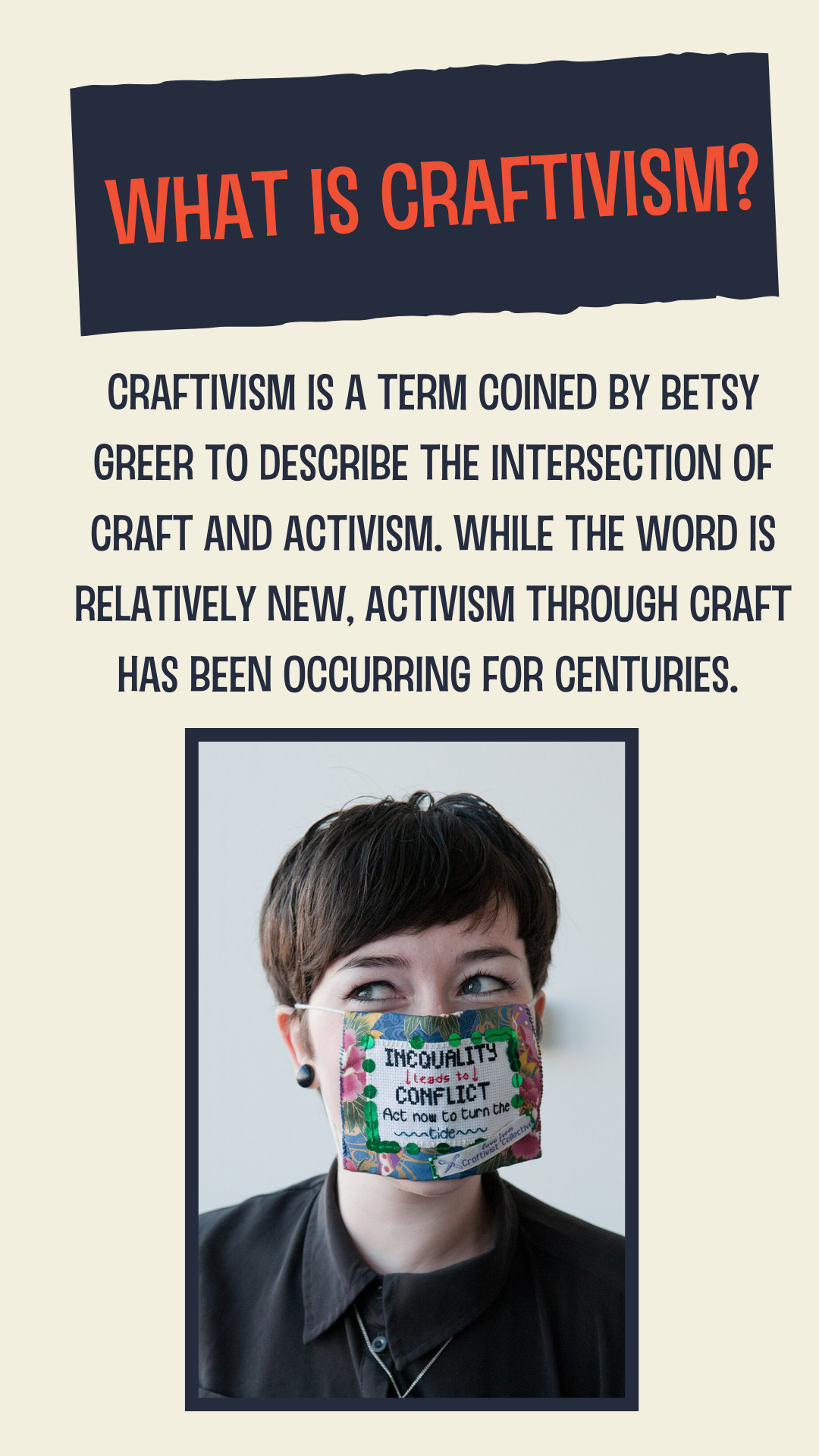

It’s an election year, so it felt like a good time to talk about “craftivisim,” a term that was coined in 2014 but describes something that has existed for centuries. In 2014, Betsy Greer coined the term “Craftivism.” In her book, Greer gave a name to the intersection of craft and activism, looking at places where crafters and artists want their work to contribute to the greater good, spark conversation, and signal their activism to the wider world.

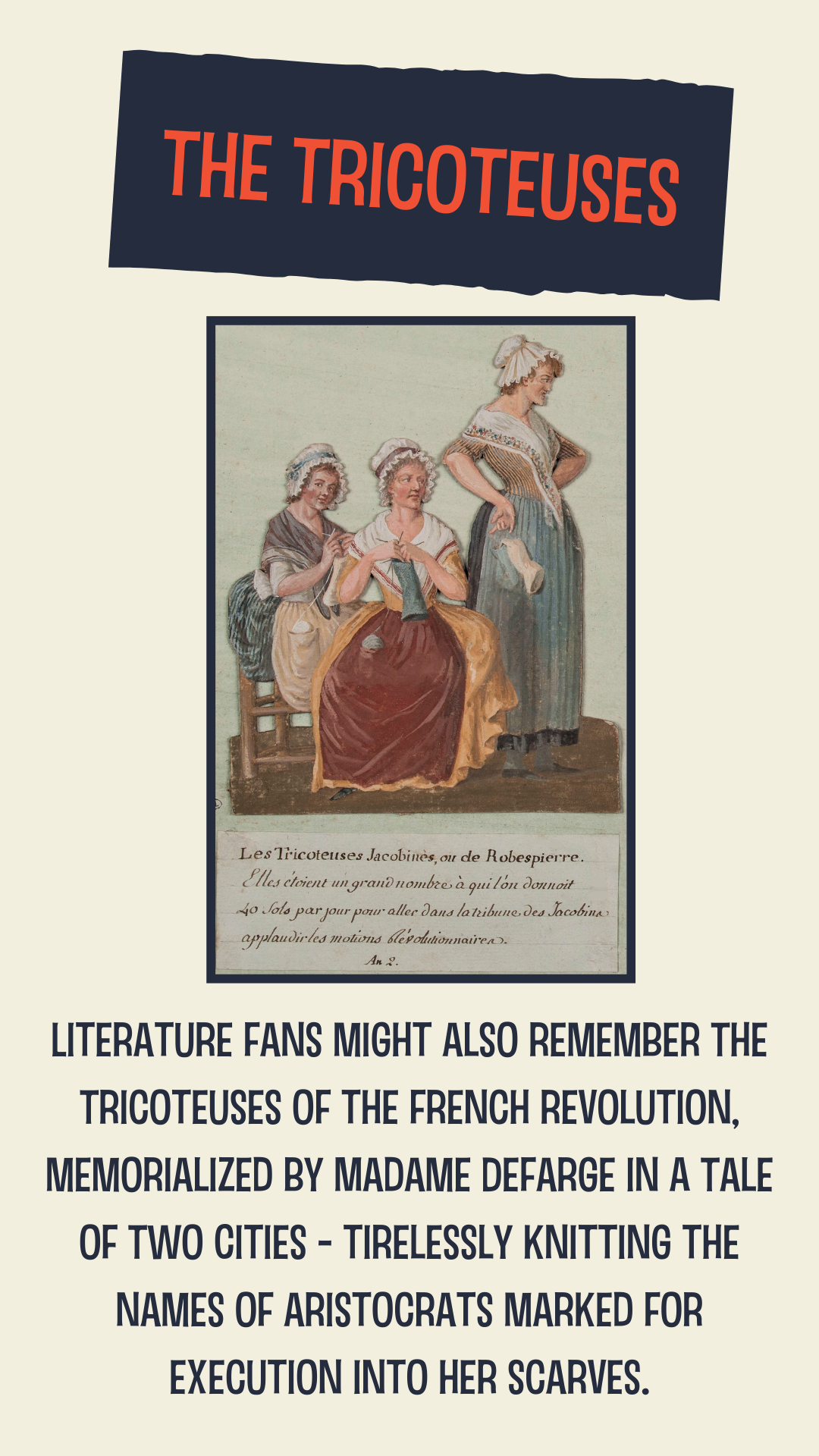

In the ten years since Greer gave us a word for this movement, we have seen global waves of pink pussy hats, and welcome blankets for immigrants, but crafters know there has been a long history of using their practice to inspire change and progress. Perhaps the most familiar example for us is the Tricoteuses of the French Revolution. Made famous by Charles Dickens’ Madame DeFarge in The Tale of Two Cities, the always-knitting DeFarge was keeping track of aristocrats marked for execution with her knitted scarves. Since then, the image of a woman knitting at a protest of any kind has been easily recognizable.

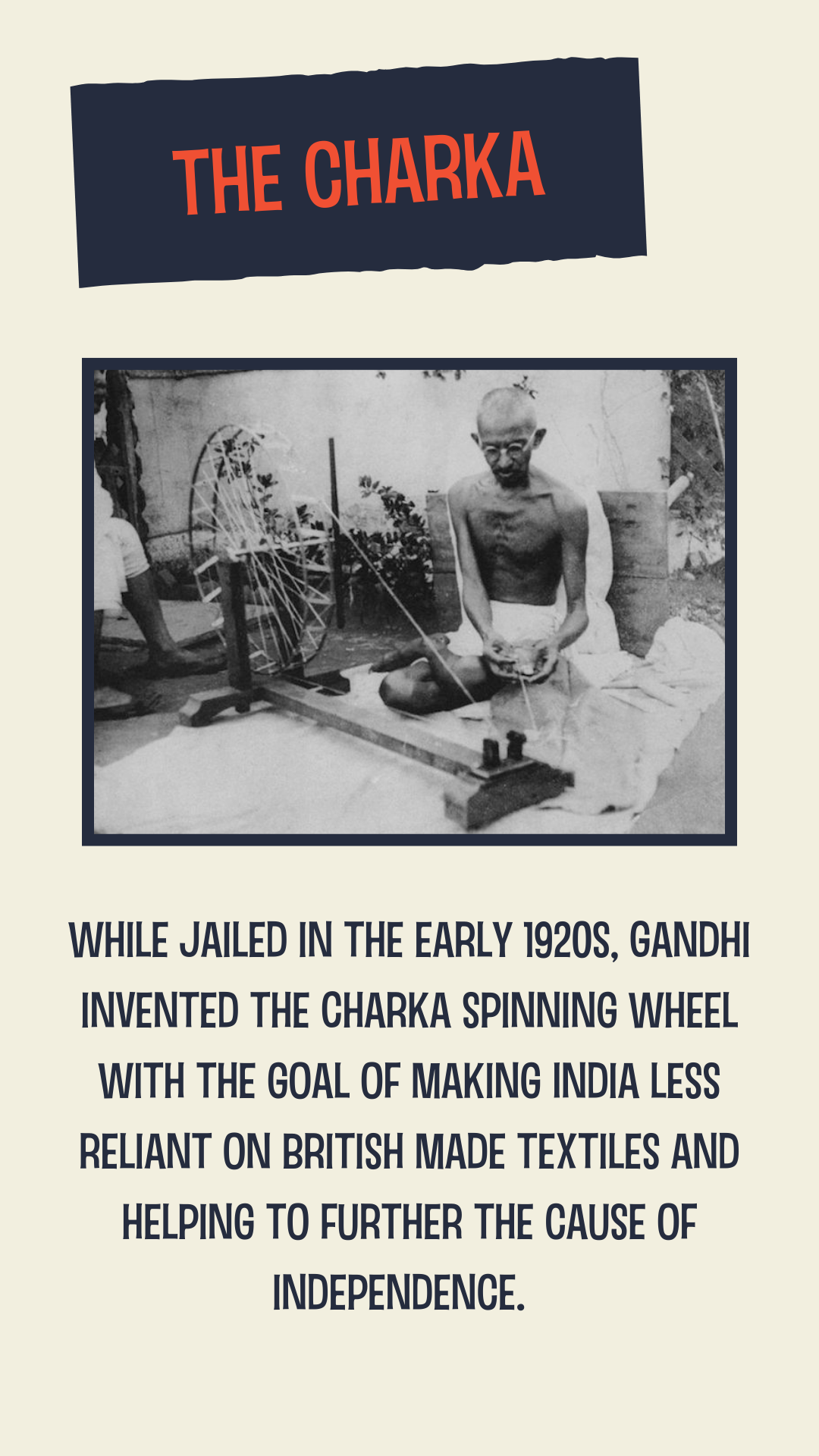

It can be easy to look at craftivism and wonder … why this medium to protest? The truth is that crafting and fiber arts are part of the much more complicated global trade. For example, in the early 1930s, Mahatma Gandhi participated in a form of Craftivism after holding a contest to invent a more efficient spinning wheel. Gandhi took a modified Charkha spinning wheel with him when he was imprisoned by the British for advocating for India’s independence. The Charkha wheel is a unique spinning wheel, portable, and ideally suited for spinning the short fibers common with cotton and linen. By spinning cotton in prison, Gandhi worked to make India less reliant on British-made textiles and to help the manufacturing of Kadhi cloth. By making spinning easier and more portable, kodhi cloth could be a uniform of self-reliance in advocating for an Independent India.

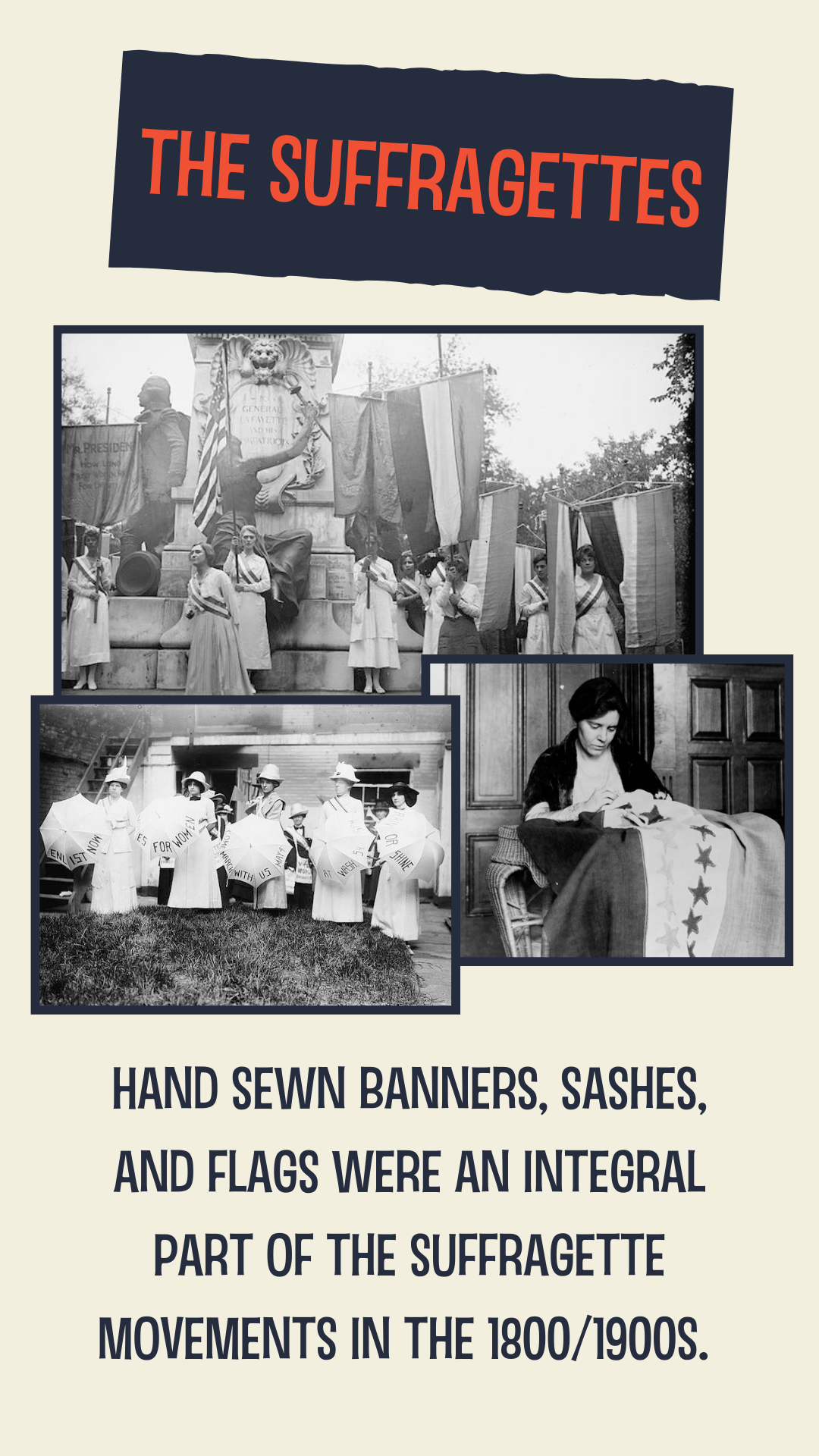

In the United States, we also see examples of craftivism in our history. The Suffragist movement from the 1800s all the way to the passage of the 23rd Amendment featured hand-sewn banners, flags and sashes from women looking for an equal right to vote.

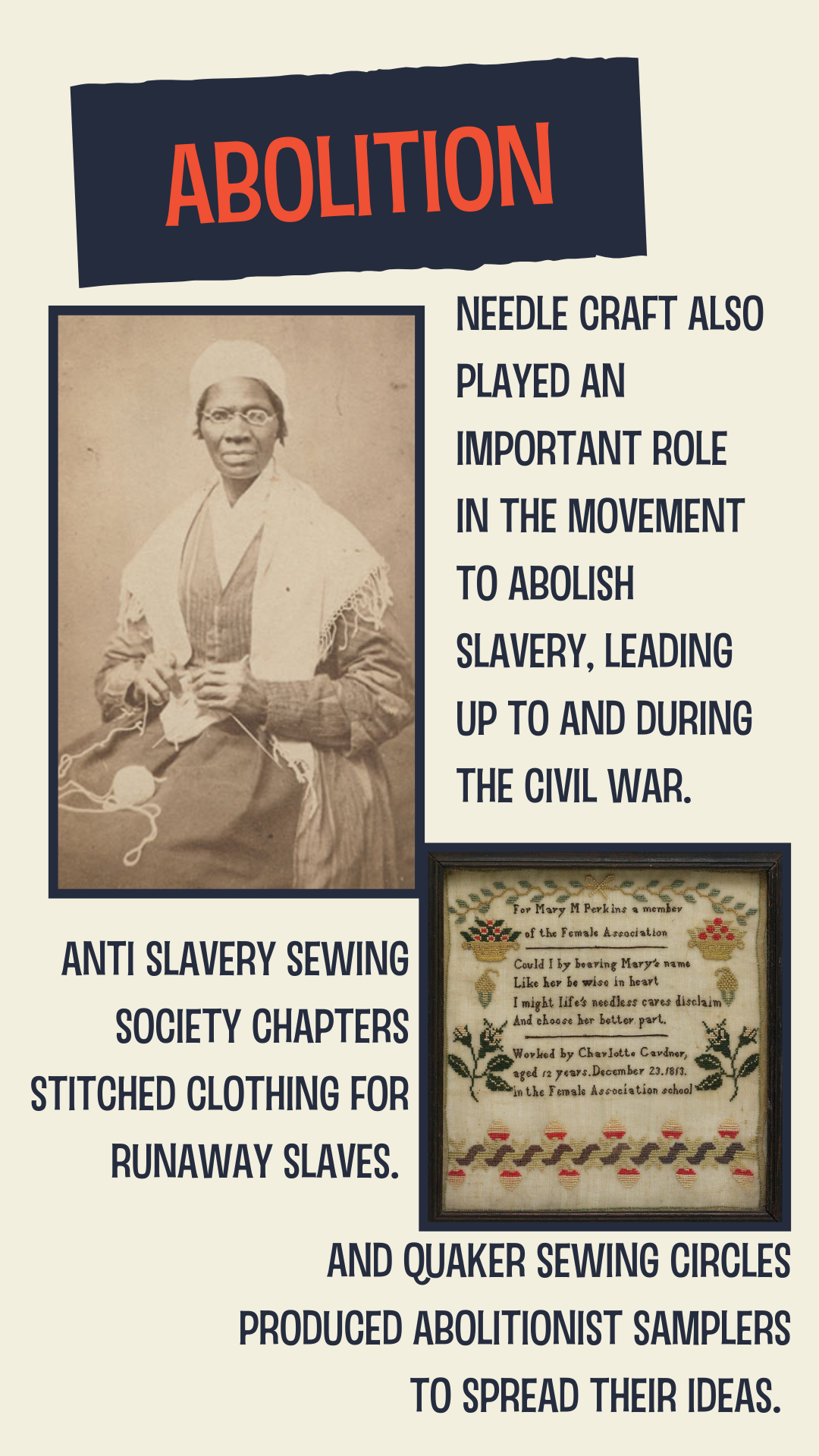

Needlecrafts are integral to the story of the abolitionist movement in the United States as well. Abolition society members would stitch clothes for runaway slaves. Sojourner Truth, one of the most vocal advocates for abolition, was also an avid knitter. She escaped slavery and spoke across the country advocating for liberation and equality. Truth notably raised money for the cause of abolition by selling cards with her photo captioned with "I Sell the Shadow to Support the Substance.” In this photo, Truth is seated, a shawl draped around her shoulders, and pausing in her knitting. We can see her double points at rest, seemingly halfway through a hat. Other portraits of Truth feature her holding her needles, always part way through her projects, the work ongoing.

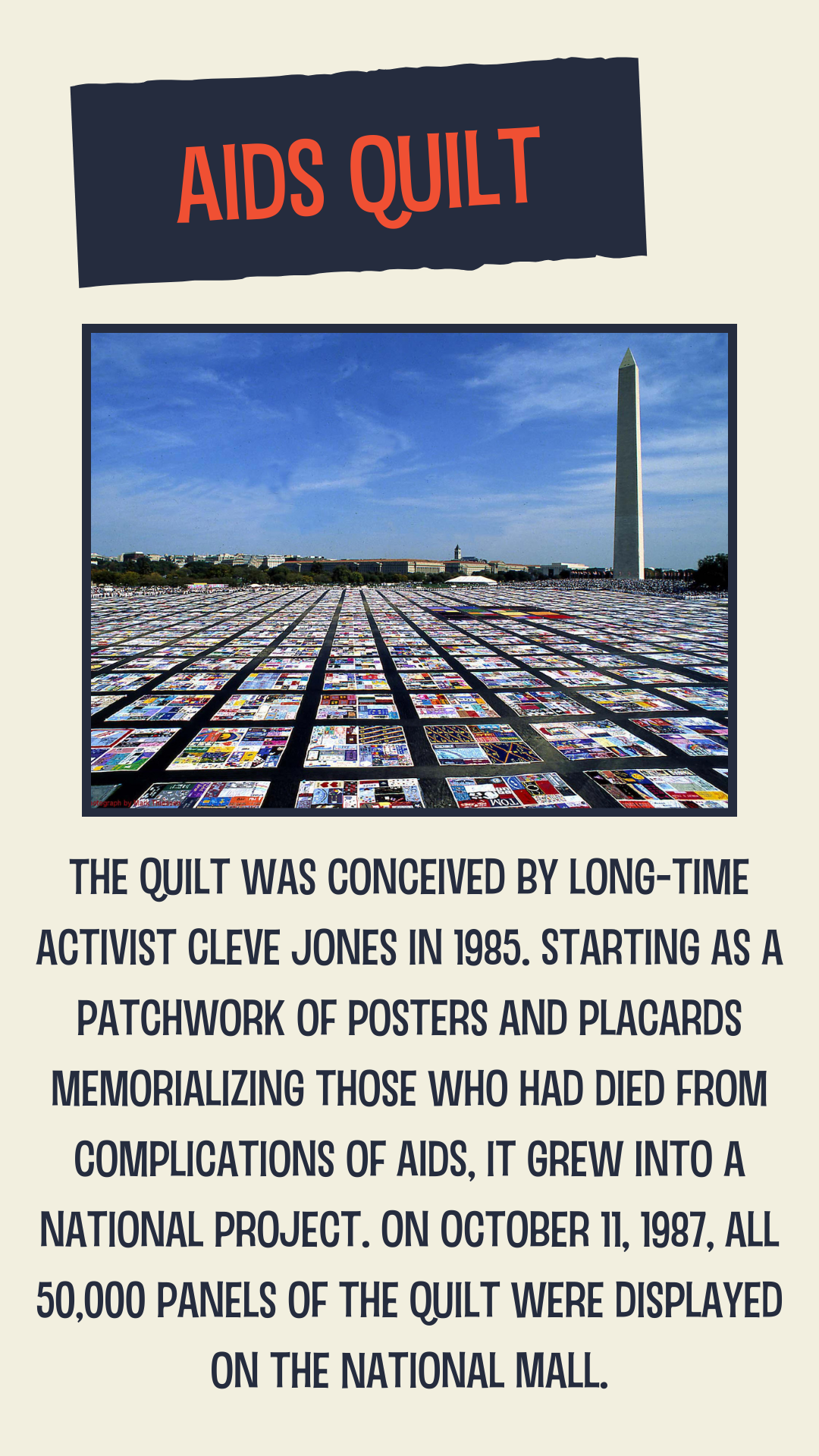

Many of us remember the startling and sobering image of the AIDS quilt in the 1980s. The largest public art and communal crafting project in history, the Quilt is an ongoing effort to memorialize those who have lost the fight with AIDS. Conceived by long-time activist Cleve Jones in 1985, the AIDS quilt began first as a patchwork of posters and placards to commemorate those who passed from complications from AIDS. The medium eventually shifted to the much more durable fabric quilt format. This small art project grew into a national movement, and on October 11, 1987, 1,920 panels were displayed in the heart of Washington, DC, covering the National Mall with a patchwork of loss. Today the AIDS Quilt continues to grow and is up to 50,000 panels.

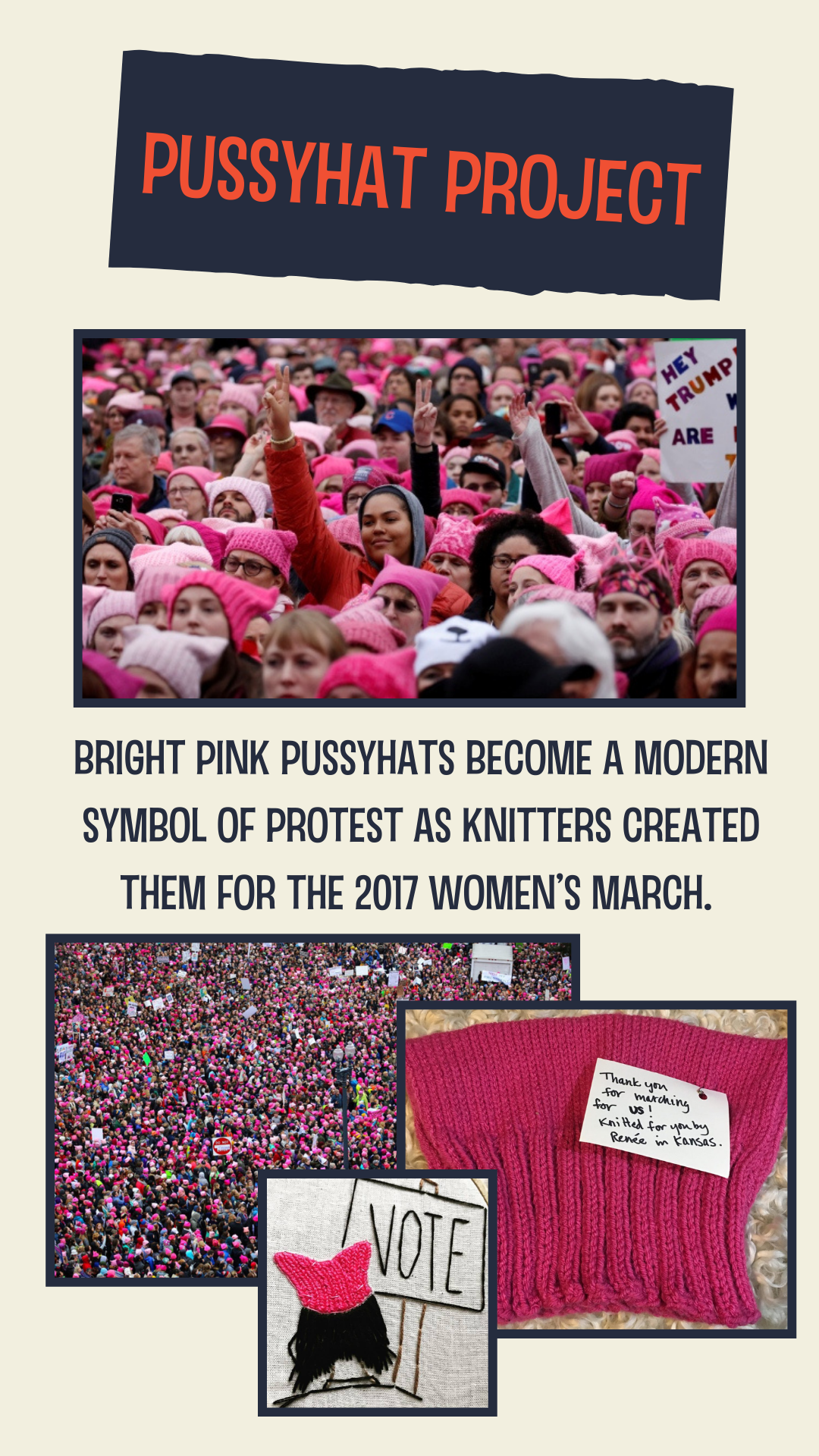

Nearly 8 years ago after the first election of Donald Trump to the White House, the D.C. area saw a sea of pink at the Women’s March. Thousands wore handmade bright pink Pussy Hats to march in protest and for women’s rights. The global movement began with a simple hat and inspired knitters to take up their needles for the community. Our shop was a pick up location for the hats, providing residents of the DC area with a chance to get a handmade hat from a knitter or crocheter who mailed hats to provide warmth and inspiration to those marching. The hats came with handwritten notes, indicating why the stitcher was sending along the hat and letting its recipients know that they were marching for their rights as well. The Pussy Hat remains a visible icon of feminism in the United States.

“Craftivism continues to evolve to meet the challenges and issues of the age. Climate change, ethical labor practices and reproductive freedom are all vital issues that crafters have taken to stitching their position on. For hobbies that are still dismissed or reduced to “women’s work,” crafters are a powerful community, unafraid to express themselves.”